This is not the most detailed or insightful interviews with Stan Lee, but one that few people have seen. It was done in 2015 making one of the last interviews of this type that Stan had done.

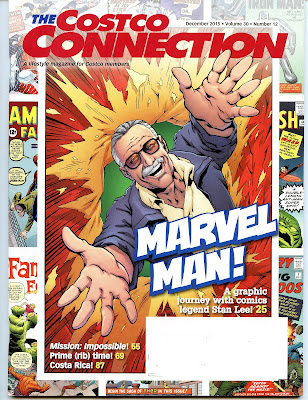

It was one for Costco in a publication they call “The Costco Connection and was conducted by J. Rentilly.

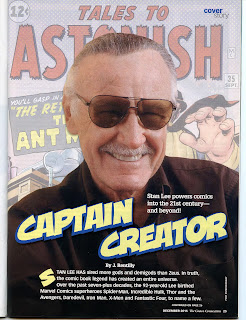

STAN LEE has sired more gods and demigods than Zeus. In truth, the comic book legend has created an entire universe. Over the past seven-plus decades, the 92-year-old Lee birthed Marvel Comics superheroes Spider-Man, Incredible Hulk, Thor and the Avengers, Daredevil, Iron Man, X-Men and Fantastic Four, to name a few.

In the process, he introduced a new breed of mythical comic creatures. He created a menagerie of mutants, outcasts, rebels and misfits in the service of saving the galaxy from pandemonium and otherworldly interlopers, who at the same time dealt with the zeitgeist's most pressing issues—from drug addiction to civil rights, Cold War paranoia to women’s liberation, psychological frailties and aberrations to acne. What made them unique as superheroes were their attempts at self-‑ improvement and their collection of character flaws. Lee's gallery of char acters may be able to spin webs or take flight, but their personal lives tend toward vales of sorrow.

In the 1960s Lee was a major force in the publishing industry establishing Marvel Comics as a cultural juggernaut that in 1965 sold 32 million books, ushering in the so‑ called Silver Age of Comics with his unique amalgam of classic mythology, Victorian and Romantic tropes, operatic grandeur and psychotherapy. From Lee's fertile imagination cascaded indelible, influential narratives and a roll call of some of contemporary literature's most enduring characters.

Lee's revolutionary tenure at Marvel has been bested only by his triumphs in the motion picture industry, where he was recently crowned the most successful filmmaker of all time, owing to the $15 billion worldwide grossed by movies featuring his eccentric scions.

Born into poverty as Stanley Martin Lieber and growing up during the Great Depression, Lee landed a gig at Timely Comics in 1939, when he was 17 years old, filling inkwells for staff writers and artists. A voracious reader, he took the job with the sole intention of providing some money to help his struggling family, while he dreamed of one day penning the Great American Novel.

Within two years, at the age of 19, he was improbably named the company's interim editor, and promptly authored a Captain America Comics adventure and then hatched his first original protagonist, the Destroyer.

The rest, as they say, is history.

When The Connection catches up with the robust nonagenarian bard in sunny Southern California, he's wearing a mint green V-neck sweater over a white dress shirt. His bountiful white mane is vigorously slicked back. Despite being enswathed in his trademark sunglasses (his own version of a superhero's mask, he concedes), Lee's eyes remain visible and positively radiant, scintillating at several topics of conversation, including his personal origin story; Joan Clayton Boocock, the "love of his life," whom he married nearly seven decades ago; and his upcoming slate, including Chakra the Invincible and The Zodiac Legacy, two new comics titles, and a jocular, often intimate, lushly illustrated graphic-novel-style autobiography, Amazing Fantastic Incredible: A Marvelous Memoir.

In his modest Beverly Hills office, Lee speaks in the burst balloons and boldface, teasing ellipses of comic book dialogue itself, shuffling together wisecracks and wisdom but with a sincere incredulousness that he has lived, for nearly a century, a life, well, amazing, fantastic and incredible.

The Costco Connection: The psychological complexity of your superheroes sets them apart in the world of comics, particularly when they began appearing half a century ago.

Stan Lee: Well, I'm not 100 percent sure about this, but I don't think most human beings can fly or swing through a big city on spiderwebs, but we all know something about fear and loss and feeling powerless, don't we?

CC: So much creativity comes from strife or hardship in the creator's life. Do you feel your characters were, in some ways, born of the challenges of your youth?

SL: I think everybody is a product of the life he or she leads. In my case, my parents didn't have much money. My father was unemployed a lot of the time. This was the Great Depression; you have to remember. We lived in this very tiny apartment in the Bronx, hand to mouth. We were one of the only families living in our building that didn't even have a car. Reading was one of the most inexpensive forms of pleasure at the time; you could always get a good story at the library—for free! Going to a movie, I think, cost a quarter, which was a lot of money at the time. So I read. Anything. Everything. All the time. One of the best gifts I ever received came from my parents when I was a little boy. They got me this little bookstand for Christmas so I could put the book in front of me and read while I was eating. I think that gift was my mother's idea; she was worried what would happen to me if all I ever read in the house were ketchup bottles and cereal boxes. I still think that's some of the best literature out there.

CC: Would you say that some of your characters are at least partially autobiographical?

SL: I don't know, really. When I was writing those characters, I was never consciously thinking about my own life or experiences. I was just making things up. But maybe you're right.

CC: When did you realize that your true calling in hfe was as a storyteller?

SL: I don't think I ever realized it. I got into comic books for no other reason than I really needed a job. Before that, I was an office boy. I wrote ad copy for a hospital. I delivered sandwiches for a drugstore. I was an errand boy for the second-largest trouser manufacturer in the country. I wrote obituaries for the local newspaper. I was an usher at the Rivoli Theatre, which I loved because I could watch the movies for free. I wanted to be one of those big-screen heroes, like John Wayne or Errol Flynn. I wanted swagger. But I was too skinny.

CC: Your earliest responsibilities at Timely Comics were not exactly glamorous.

SL: I was hired to be an assistant to Joe Simon and Jack Kirby [the team who created Captain America], which must be one of the most amazing things that happened in my life, next to meeting my wife. Can you imagine working for geniuses like that? I filled the inkwells. I brought them sandwiches. I erased the penciled pages after they'd been inked. Eventually, they saw that I could write. One day, the publisher came into the office and asked me if I could look after things until he could hire a grown-up because he needed an interim editor. I don't know if I was a grown- up or not, but that's how I started writing stories, working with artists, doing my thing.

CC: When it came to your byline, you changed your name from Stanley Martin Lieber to Stan Lee. Why?

SL: Well, I did it because I was embarrassed to be doing comics! People had so little respect for comic books that I didn't want anybody to know who I really was. Comics were just dumb little kids' stories with pictures, right? Even I thought that for a while. Once I realized how easy writing was—at least for me—I figured, "I've gotta get out of this comics thing. I'm going to write the Great American Novel!"

CC: You merged classic mythology with contemporary psychology, which was revolutionary stuff then. Why do you think your comic books have connected so meaningfully with readers?

SL: Every young person loves fairy tales, witches, giants, wizards, the things that are bigger and more colorful than real life. They're "what if" stories, which we love. Which I think we need. What if a man could fly? What if this, that and the other thing? But we reach an age in our teen years where we're told to stop reading fairy tales, that we're too old for all of that magic and wonder. I don't agree with that. So the comics I started writing were, basically, comic books for older people, fairy tales for adults—or smart people, anyway. I also really tried to write these characters so that readers believed they were actually alive and doing these things and maybe somehow sharing the world with you and me.

CC: Has your writing process changed much through the years?

SL: Well, I don't stand as much now as I used to. [Laughs] See, I love the sun. I also really didn't want to become one of those writers who got a big potbelly because he's sitting at a desk all the time. So when I was writing a lot of these stories, back in the '60s and '70s, I put this bridge table out on the terrace—this was at our house in Long Island, a long time ago—and then I put a little stool on top of that so it was tall enough and then I'd put my typewriter on top of that. That way, I could stand outside in the sun and type all day long. And my wife would have these little parties at the house and everyone would be talking and drinking and laughing all around me, and I'd just be standing there, typing away. She really is the perfect wife for me.

CC: There are infinite theories about where creative ideas come from. Where do you think Ant-Man, Scarlet Witch or even the Destroyer, your very first comic book hero, comes from?

SL: Well, you just think about it! You just sit down or walk around and probably have a big, dumb look on your face and you wonder, "What would I like to read? What kind of character would interest me?" I'm asked a lot what tips I would give to other writers. The truth is: I don't know any tips. I can't think of a single tip.

Now I've been writing long enough to have met an awful lot of writers who sit down at their computer or whatever and say, "OK, now I'm going to write the story for young ladies, aged 17 to 26: I don't have a clue how to do that. I don't know what other people want; I know what I want. So the only thing I can say when answering that question is:

Please write stories that you think are great. Write to please yourself. That's how I've always done it—not because I'm so desperate to please other people, but because I fee] very genuinely that if I really love a story, then there must be a few other people out there who would love it too. I'm not that special.

CC: Writing an autobiography is, necessarily, a process of reflection. Looking back at your life on the verge of 93, does it really feel like an amazing, fantastic, incredible life?

SL: If I said anything but "yes, absolutely," I am sure I would sound like a terrible human being. But it's funny, when I look back at those days in Long Island, I remember the feelings I had then of being just a little bit unhappy because, mostly, there were three kinds of comic book people in the world back then. There were the people who thought comic books were stupid and unimportant, and there were people who just didn't care about comic books at all. And then there were the people who actually read them. We were living in Long Island, surrounded by stockbrokers and doctors and lawyers and businessmen, and there I was, writing these little stories with drawings in them, and I couldn't let go of the idea that most people didn't give a damn about the work I was doing. I wasn't winning important court cases. I wasn't healing people's bodies. I wasn't changing anyone's world. It was a lousy feeling in those days.

CC: The evidence by now has surely changed your mind about that, yes?

SL: Well, as the years went by, I realized that entertainment is one of the most important things in the world. People need it. They really need it. That's why they go to concerts and movies and read books and watch television. Life is tough for a lot of people. If you can do something that brings someone else just a little bit of relief or pleasure—like telling them a really great story, maybe—that's not a bad thing to do, right? So, over the years, I've learned to be happy with the work I do, rather than apologetic for it.

CC: Good! One more question. Who do you think is better-looking: Stan Lee in real

life or the illustrated Stan Lee in Amazing Fantastic Incredible?

SL: Oh, that's easy. Me! I'm much better-looking. The hair is so much thicker. Look at me!

In the process, he introduced a new breed of mythical comic creatures. He created a menagerie of mutants, outcasts, rebels and misfits in the service of saving the galaxy from pandemonium and otherworldly interlopers, who at the same time dealt with the zeitgeist's most pressing issues—from drug addiction to civil rights, Cold War paranoia to women’s liberation, psychological frailties and aberrations to acne. What made them unique as superheroes were their attempts at self-‑ improvement and their collection of character flaws. Lee's gallery of char acters may be able to spin webs or take flight, but their personal lives tend toward vales of sorrow.

In the 1960s Lee was a major force in the publishing industry establishing Marvel Comics as a cultural juggernaut that in 1965 sold 32 million books, ushering in the so‑ called Silver Age of Comics with his unique amalgam of classic mythology, Victorian and Romantic tropes, operatic grandeur and psychotherapy. From Lee's fertile imagination cascaded indelible, influential narratives and a roll call of some of contemporary literature's most enduring characters.

Lee's revolutionary tenure at Marvel has been bested only by his triumphs in the motion picture industry, where he was recently crowned the most successful filmmaker of all time, owing to the $15 billion worldwide grossed by movies featuring his eccentric scions.

Born into poverty as Stanley Martin Lieber and growing up during the Great Depression, Lee landed a gig at Timely Comics in 1939, when he was 17 years old, filling inkwells for staff writers and artists. A voracious reader, he took the job with the sole intention of providing some money to help his struggling family, while he dreamed of one day penning the Great American Novel.

Within two years, at the age of 19, he was improbably named the company's interim editor, and promptly authored a Captain America Comics adventure and then hatched his first original protagonist, the Destroyer.

The rest, as they say, is history.

When The Connection catches up with the robust nonagenarian bard in sunny Southern California, he's wearing a mint green V-neck sweater over a white dress shirt. His bountiful white mane is vigorously slicked back. Despite being enswathed in his trademark sunglasses (his own version of a superhero's mask, he concedes), Lee's eyes remain visible and positively radiant, scintillating at several topics of conversation, including his personal origin story; Joan Clayton Boocock, the "love of his life," whom he married nearly seven decades ago; and his upcoming slate, including Chakra the Invincible and The Zodiac Legacy, two new comics titles, and a jocular, often intimate, lushly illustrated graphic-novel-style autobiography, Amazing Fantastic Incredible: A Marvelous Memoir.

In his modest Beverly Hills office, Lee speaks in the burst balloons and boldface, teasing ellipses of comic book dialogue itself, shuffling together wisecracks and wisdom but with a sincere incredulousness that he has lived, for nearly a century, a life, well, amazing, fantastic and incredible.

The Costco Connection: The psychological complexity of your superheroes sets them apart in the world of comics, particularly when they began appearing half a century ago.

Stan Lee: Well, I'm not 100 percent sure about this, but I don't think most human beings can fly or swing through a big city on spiderwebs, but we all know something about fear and loss and feeling powerless, don't we?

CC: So much creativity comes from strife or hardship in the creator's life. Do you feel your characters were, in some ways, born of the challenges of your youth?

SL: I think everybody is a product of the life he or she leads. In my case, my parents didn't have much money. My father was unemployed a lot of the time. This was the Great Depression; you have to remember. We lived in this very tiny apartment in the Bronx, hand to mouth. We were one of the only families living in our building that didn't even have a car. Reading was one of the most inexpensive forms of pleasure at the time; you could always get a good story at the library—for free! Going to a movie, I think, cost a quarter, which was a lot of money at the time. So I read. Anything. Everything. All the time. One of the best gifts I ever received came from my parents when I was a little boy. They got me this little bookstand for Christmas so I could put the book in front of me and read while I was eating. I think that gift was my mother's idea; she was worried what would happen to me if all I ever read in the house were ketchup bottles and cereal boxes. I still think that's some of the best literature out there.

CC: Would you say that some of your characters are at least partially autobiographical?

SL: I don't know, really. When I was writing those characters, I was never consciously thinking about my own life or experiences. I was just making things up. But maybe you're right.

CC: When did you realize that your true calling in hfe was as a storyteller?

SL: I don't think I ever realized it. I got into comic books for no other reason than I really needed a job. Before that, I was an office boy. I wrote ad copy for a hospital. I delivered sandwiches for a drugstore. I was an errand boy for the second-largest trouser manufacturer in the country. I wrote obituaries for the local newspaper. I was an usher at the Rivoli Theatre, which I loved because I could watch the movies for free. I wanted to be one of those big-screen heroes, like John Wayne or Errol Flynn. I wanted swagger. But I was too skinny.

CC: Your earliest responsibilities at Timely Comics were not exactly glamorous.

SL: I was hired to be an assistant to Joe Simon and Jack Kirby [the team who created Captain America], which must be one of the most amazing things that happened in my life, next to meeting my wife. Can you imagine working for geniuses like that? I filled the inkwells. I brought them sandwiches. I erased the penciled pages after they'd been inked. Eventually, they saw that I could write. One day, the publisher came into the office and asked me if I could look after things until he could hire a grown-up because he needed an interim editor. I don't know if I was a grown- up or not, but that's how I started writing stories, working with artists, doing my thing.

CC: When it came to your byline, you changed your name from Stanley Martin Lieber to Stan Lee. Why?

SL: Well, I did it because I was embarrassed to be doing comics! People had so little respect for comic books that I didn't want anybody to know who I really was. Comics were just dumb little kids' stories with pictures, right? Even I thought that for a while. Once I realized how easy writing was—at least for me—I figured, "I've gotta get out of this comics thing. I'm going to write the Great American Novel!"

CC: You merged classic mythology with contemporary psychology, which was revolutionary stuff then. Why do you think your comic books have connected so meaningfully with readers?

SL: Every young person loves fairy tales, witches, giants, wizards, the things that are bigger and more colorful than real life. They're "what if" stories, which we love. Which I think we need. What if a man could fly? What if this, that and the other thing? But we reach an age in our teen years where we're told to stop reading fairy tales, that we're too old for all of that magic and wonder. I don't agree with that. So the comics I started writing were, basically, comic books for older people, fairy tales for adults—or smart people, anyway. I also really tried to write these characters so that readers believed they were actually alive and doing these things and maybe somehow sharing the world with you and me.

CC: Has your writing process changed much through the years?

SL: Well, I don't stand as much now as I used to. [Laughs] See, I love the sun. I also really didn't want to become one of those writers who got a big potbelly because he's sitting at a desk all the time. So when I was writing a lot of these stories, back in the '60s and '70s, I put this bridge table out on the terrace—this was at our house in Long Island, a long time ago—and then I put a little stool on top of that so it was tall enough and then I'd put my typewriter on top of that. That way, I could stand outside in the sun and type all day long. And my wife would have these little parties at the house and everyone would be talking and drinking and laughing all around me, and I'd just be standing there, typing away. She really is the perfect wife for me.

CC: There are infinite theories about where creative ideas come from. Where do you think Ant-Man, Scarlet Witch or even the Destroyer, your very first comic book hero, comes from?

SL: Well, you just think about it! You just sit down or walk around and probably have a big, dumb look on your face and you wonder, "What would I like to read? What kind of character would interest me?" I'm asked a lot what tips I would give to other writers. The truth is: I don't know any tips. I can't think of a single tip.

Now I've been writing long enough to have met an awful lot of writers who sit down at their computer or whatever and say, "OK, now I'm going to write the story for young ladies, aged 17 to 26: I don't have a clue how to do that. I don't know what other people want; I know what I want. So the only thing I can say when answering that question is:

Please write stories that you think are great. Write to please yourself. That's how I've always done it—not because I'm so desperate to please other people, but because I fee] very genuinely that if I really love a story, then there must be a few other people out there who would love it too. I'm not that special.

CC: Writing an autobiography is, necessarily, a process of reflection. Looking back at your life on the verge of 93, does it really feel like an amazing, fantastic, incredible life?

SL: If I said anything but "yes, absolutely," I am sure I would sound like a terrible human being. But it's funny, when I look back at those days in Long Island, I remember the feelings I had then of being just a little bit unhappy because, mostly, there were three kinds of comic book people in the world back then. There were the people who thought comic books were stupid and unimportant, and there were people who just didn't care about comic books at all. And then there were the people who actually read them. We were living in Long Island, surrounded by stockbrokers and doctors and lawyers and businessmen, and there I was, writing these little stories with drawings in them, and I couldn't let go of the idea that most people didn't give a damn about the work I was doing. I wasn't winning important court cases. I wasn't healing people's bodies. I wasn't changing anyone's world. It was a lousy feeling in those days.

CC: The evidence by now has surely changed your mind about that, yes?

SL: Well, as the years went by, I realized that entertainment is one of the most important things in the world. People need it. They really need it. That's why they go to concerts and movies and read books and watch television. Life is tough for a lot of people. If you can do something that brings someone else just a little bit of relief or pleasure—like telling them a really great story, maybe—that's not a bad thing to do, right? So, over the years, I've learned to be happy with the work I do, rather than apologetic for it.

CC: Good! One more question. Who do you think is better-looking: Stan Lee in real

life or the illustrated Stan Lee in Amazing Fantastic Incredible?

SL: Oh, that's easy. Me! I'm much better-looking. The hair is so much thicker. Look at me!