It was a different world in 1971.

Among many things, this article shows an optimistic Jack Kirby and

Carmine Infantino discussing Kirby’s Fourth World. And we discover how much

money Jack Kirby was earning when he left Marvel. Martin

Goodman, who was rarely interviewed, speaks here. So does Roy Thomas and Stan

Lee. There is a mistake, Marvel was selling 70 million comics a year at this

point and the article says 40. And at the end, we get a letter to the editor from cartoonist

New

York Times May 2, 1971

SAUL

BRAUN is a freelance writer who says he’ll probably never stop reading comic

books.

Envision

a scene in a comic book:

In Panel I, two New York City policemen are pointing

skyward with their jaws hanging open and one is saying, “Wha . . .?” They are

looking at four or five men and women, shown in Panel 2 plummeting through the

air feet first, as though riding surfboards. The dominant figure has a black

long coat thrown over his shoulders, wears a peaked, flat-brim hat and carries

a cane. As the group lands on the street and enters the “Vision Building,”

Panel 3, a hairy hip figure on the sidewalk observes to a friend: “Fellini’s in

town.”

In Panel 4, an office interior, the man with the cape

is saying to the secretary, “I am Federico Fellini, come to pay his respects to

...” Turn the page and there is the Fellini figure in the background finishing

his balloon: “... the amazing Start Lee.” In the foreground is a tail, skinny

man with a black D. H. Lawrence beard, wearing bathing trunks, long-sleeved

turtleneck sweater and misshapen sailor hat. Stan Lee stands alongside a table

that has been piled on another table, and on top of that is a typewriter with a

manuscript page inserted in it that reads: “The Amazing Spider-Man. In the Grip

of the Goblin! It’s happening again. As we saw last....”

THIS visit, in more mundane fashion, actually took place. Stan Lee has

been writing comic books for 30 years and is now editor-in-chief of the Marvel

Comics line. His reputation with cognoscenti is very, very high.

Alain Resnais is also a Lee fan and the two are now working together on

a movie. Lee has succeeded so well with his art that he has spent a good deal

of his time traveling around the country speaking at colleges. In his office at

home—which is currently a Manhattan apartment in the East 60’s—he has several

shelves filled with tapes of his college talks. An Ivy League student was once

quoted as telling him, “We think of Marvel Comics as the 20th century mythology

and you as this generation’s Homer.”

Lee’s comic antiheroes (Spider-Man,

Fantastic Four, Submariner, Thor, Captain America) have revolutionized an

industry that took a beating from its critics and from TV in the

nineteen-fifties. For decades, comic book writers and artists were considered

little more than production workers, virtually interchangeable. Now Lee and his

former collaborator, artist Jack Kirby of National Comics, Marvel’s principal

rival, are considered superstars—and their work reflects a growing sophistication

in the industry that has attracted both young and old readers.

“We’re in a renaissance,” says Carmine Infantino, editorial director at

National Comics, and he offers as proof the fact that at Brown University in

Providence, R.I., they have a course, proposed by the students called

“Comparative Comics.” A prospectus for the course sets out the case for comic

books as Native Art:

“Comics, long scorned by parents, educators, psychologists, lawmakers,

American Legionnaires, moral crusaders, civic groups and J. Edgar Hoover, have

developed into a new and interesting art form. Combining new journalism’ with

greater illustrative realism, comics are a reflection of both real society and

personal fantasy. No longer restricted to simple, good vs. evil plot lines and unimaginative,

sticklike figures, comics can now be read at several different levels by

various age groups. There are still heroes for the younger readers, but now the

heroes are different—they ponder moral questions, have emotional differences,

and are just as neurotic as real people. Captain America openly sympathizes

with campus radicals, the Black Widow fights side by side with the Young Lords,

Lois Lane apes John Howard Griffin and turns herself black to study racism, and

everybody battles to save the environment.”

As

for Fellini, his interest in American comic books, and Stan Lee’s work in

particular, is no passing fancy. For an introduction to Steranko’s “History of

the Comics,” he wrote the following lines:

“Not

satisfied being heroes, but becoming even more heroic, the characters in the

Marvel group know how to laugh at themselves. Their adventures are offered

publicly like a larger-than-life spectacle, each searching masochistically

within himself to find a sort of maturity, yet the results are nothing to be

avoided: it is a brilliant tale, aggressive and retaliatory, a tale that

continues to be reborn for eternity, without fear of obstacles or paradoxes. We

cannot die from obstacles and paradoxes, if we face them with laughter. Only of

boredom might we perish. And from boredom, fortunately, the comics keep a

distance.”

For

an industry that wields considerable influence, comic-book publishing has only

a small fraternity of workers. There are something like 200 million comic books

sold each year, a volume produced by less than 200 people, including writers,

artists and letterers. The artists fall into two categories, pencillers and

inkers. Pencillers are slightly more highly reputed than inkers but, with few

exceptions, nobody in the business has much of a public reputation, and most

are poorly compensated. Most are freelancers, paid at a page rate that the

various publishers prefer not to divulge. A rate of $15 a page, however, is

said to be not uncommon.

“This is a fiercely competitive business,” says Infantino. “After

Superman clicked in 1938 everybody jumped in; there were millions of outfits.

Then one by one they all slipped away. When World War II ended, then came

survival of the fittest and, boom, they died by the wayside.”

As in other industries, power gradually became concentrated during the

nineteen-fifties and sixties, and now the industry consists of perhaps half a

dozen companies with annual sales of about 200 million. National, the leader,

sells about 70 million. Marvel sells 40 million, Archie 35 million, and the

next three firms—Charlton (Yogi Bear, Beetle Bailey, Flintstones), Gold Key

(Bugs Bunny, Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse) and Harvey (Caspar the Friendly Ghost,

Richie Rich, Sad Sack) each sell about 25 million. That is a great many copies,

but doesn’t necessarily reflect profitability. The index of profit and loss is

not sales but the percentage of published copies that are returned unsold from

the store racks. A book that suffers returns of more than 50 per cent is in

trouble.

Martin Goodman, president of the Magazine Management Company, which puts

out the Marvel line, recalls that the golden age of comics was the war years

and immediately afterwards. By the late forties, he says, “everything began to

collapse. TV was kicking the hell out of a great number of comics. A book like

Donald Duck went from 21/4 million monthly sale to about 200,000. You couldn’t

give the animated stuff away, the Disney stuff, because of TV. TV murdered it.

Because if a kid spends Saturday morning looking at the stuff, what parent is

going to give the kid another couple of dimes to buy the same thing again?

“Industry wide,” says Goodman sorrowfully, “the volume is not going up.

I think the comic-book field suffers from the same thing TV does. After a few

years, an erosion sets in. You still maintain loyal readers, but you lose a lot

more readers than you’re picking up. That’s why, we have so many superhero

characters, and run superheroes together. Even if you take two characters that

are weak sellers and run them together in the same book, somehow,

psychologically, the reader feels he’s getting more. You get the Avenger

follower and the Submariner follower. Often you see a new title do great on the

first issue and then it begins to slide off ...”

Goodman recalls with avuncular diffidence the arrival of Stan Lee at

Marvel, then called Timely Comics. “Stan started as a kid here; he’s my wife’s

cousin. That was in 1941, something like that. He came in as an apprentice, to

learn the business. He had a talent for writing. I think when Stan developed

the Marvel superheroes he did a very good job, and he got a lot of college kids

reading us. They make up a segment of our readership, but when you play it to

them you lose the very young kids who just can’t follow the whole damn thing.

We try to keep a balance. Because I read some stories sometimes and I can’t

even understand them. I really can’t!”

TODAY’S superhero is about as much like his predecessors as today’s

child is like his parents. My recollection of the typical pre-World War II

child (me) is of a sensitive, lonely kid full of fantasies of power and

experiencing, at the same time, a life of endless frustration and

powerlessness. Nobody knew, of course, about the hidden power, the super

muscles rippling beneath the coarse woolen suits I had to wear that itched like

crazy. How I longed to rip off that suit. Shaz...

Comic book buffs will not need to be reminded that Shazam is the magic

name of a mysterious bald gentleman with a white beard down to his waist,

which, when spoken by newsboy Billy Batson, turns Billy into Captain Marvel.

The book didn’t last long, due to the swift, self-righteous reprisals of

National Comics, which took Captain Marvel to court for impersonating Superman.

It lasted long enough to impress upon my memory, however, that “S” stood for

Solomon’s wisdom, “H” for Hercules’s strength, “A” for Atlas’s stamina, “Z” for

Zeus’s power, “A” for Achilles’ courage and “M” for Mercury’s speed. I always

had trouble remembering the last two; like many another man, I have gone

through life saying “Shaz” to myself and getting nowhere.

So my childhood was one of repressed anger and sullen obedience and

scratching all winter long, together with an iron will that kept me from

lifting my all-powerful fist and destroying those who threatened me: Nazis,

Japs, Polish kids (mostly at Easter time), older kids, teachers and parents. My

personal favorite was Submariner. He hated everybody.

Actually, all of the early comic-book heroes perfectly mirrored my own

condition, and even provided pertinent psychological details. The parents of

superheroes were always being killed by bad men or cataclysmic upheavals over

which the heroes — let me make this one thing perfectly clear—had absolutely no

control. However, they then embarked on a guilty, relentless, lifelong pursuit

of evildoers. So many villains in so many bizarre guises only attested to the

elusiveness and prevalence of—and persistence of—superhero complicity.

Secretly powerful people, like the superheroes and me, always assumed

the guise of meekness; yet even the “real” identities were only symbols.

All-powerful Superman equaled all-powerful father. Batman’s costume disguise,

like the typical parental bluster of the time, was intended to “strike terror

into their hearts.” For “their” read not only criminal but child. Infantino,

whose National Comics publishes, among others, the long-run super hit of the

comic-book industry, Superman, believes that power is the industry’s main

motif:

“The theme of comic books is power. The villain wants power. He wants to

take over the world. Take over the other person’s mind. There’s something about

sitting in the car with the motorcycles flanking you back and front and the

world at your feet. It motivates all of us.”

FOR three decades, the social setting was an America more or less

continuously at war. At war with poverty in the thirties, with Fascism in the

early forties, and with the International Red Conspiracy in the late forties

and in the fifties. During these years there existed simultaneously, if

uneasily, in our consciousness the belief that we were uniquely strong and that

nothing would avail except the unrelenting exercise of that strength. From

wanting or being forced to take the law into our own hands during the thirties,

we moved swiftly towards believing that our security depended on taking the

whole world into our hands. That carried us from the Depression to Korea and,

eventually, in the sixties, to a confused war in which it was impossible to

tell whether we were strong or weak, in which irresponsible complacency existed

comfortably with political and social atrocities that could spring only from

secret weakness masquerading as strength.

It is not irrelevant to note that the Vietnamese war developed without

hindrance—with some few exceptions—from a generation of men flying around the

world on a fantasy-power trip, and was resisted in the main by their sons, the

generation that began rejecting the comic books of the fifties with their

sanitized, censored, surreal images of the world: a world in which “we” were

good and “they” were bad, in which lawlessness masqueraded as heroism, in which

blacks were invisible, in which, according to a survey taken in 1953 by

University of California professors, men led “active lives” but women were interested

mainly in “romantic love” and only villainous women “try to gain power and

status.” A world in which no superhero, whatever his excesses, ever doubted

that he was using his powers wisely and morally.

During this time the industry was adopting a self-censorship code of

ethics in response to the hue and cry raised by a Congressional look into the

industry’s excesses of gore and by the appearance of “Seduction of the

Innocent,” a shrill piece of psycho-criticism by a psychiatrist named Fredric

Wertham, who supported his view that the comics were a pernicious influence on

children with stories like: “A boy of 13 committed a ‘lust murder’ of a girl of

6. Arrested and jailed, he asked only for comic books.”

While it is true some publishers were printing stories with grisly and

violent elements, I must confess that I to this day find myself unable to

believe that the worst comic books could have corrupted the child’s mind as

much as the knowledge that in his own world, the world he was being educated to

join, 6 million men, women and children had only recently been killed in gas

ovens for no very good reason, and large numbers of others had died at

Hiroshima and Dresden, for only slightly better reasons. Two of my own

strongest memories of the time are of my father, who owned a candy store,

denying me the treasure trove of comics (“They’ll ruin your mind”), and of my

father, after receiving a telegram telling him that his family had been wiped

out in some concentration camp somewhere, turning ashen and falling to his

knees. So, Superman, where were you when we needed you? My mind was corrupted,

yes, and so were those of countless other children of the forties and fifties.

During this time, the only comic that held its own commercially was none

other than William M. Gaines’s “MAD.” Gaines’s defense of one of his horror

comics was the high point at hearings of the Senate subcommittee on juvenile

delinquency. The cover, depicting the severed head of a blonde, said Gaines,

would have been in bad taste “if the head were held a little higher so the neck

would show the blood dripping out,”

The industry response was the comics code, including provisions

forbidding horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust,

sadism and masochism; an authority to administer the code was created, with

power to deny the industry seal of approval to any comic book violating its

provisions. This satisfied parents and educators, but only intensified the

sales slide for seal-of-approval comic books. The turnabout came in 1961, when

Stan Lee metamorphosed the Marvel line and very likely saved comic books from

an untimely death.

OUR competitors couldn’t understand why our stuff was selling,” Lee

recalls. “They would have a superhero see a monster in the street and he’d say,

‘Oh, a creature, I must destroy him before he crushes the world.’ And they’d

have another superhero in another book see a monster and he’d say, ‘Oh, a

creature, I must destroy him before he crushes the world.’ It was so

formularized. I said to my writers, ‘Is that what you’d say in real life? If

you saw a monster coming down the street, you’d say, ‘Gee, there must be a

masquerade party going on.’

“Because sales were down and out of sheer boredom, I changed the whole

line around. New ways of talking, hang-ups, introspection and brooding. I

brought out a new magazine called ‘The Fantastic Four,’ in 1961. Goodman came

to me with sales figures. The competitors were doing well with a superhero

team. Well, I didn’t want to do anything like what they were doing, so I talked

to Jack Kirby about it. I said, ‘Let’s let them not always get along well;

let’s let them have arguments. Let’s make them talk like real people and react

like real people. Why should they all get superpowers that make them beautiful?

Let’s get a guy who becomes very ugly.’ That was The Thing. I hate heroes

anyway. Just ‘cause a guy has superpowers, why couldn’t he be a nebbish, have

sinus trouble and athlete’s foot?”

The most successful of the Stan Lee antiheroes was one Spider-Man, an

immediate hit and still the top of the Marvel line. Spidey, as he is known to

his fans, is actually Peter Parker, a teen-ager who has “the proportionate

strength of a spider,” whatever that means, and yet, in Lee’s words, “can still

lose a fight, make dumb mistakes, have acne, have trouble with girls and have

not too much money,”

In Parker’s world, nobody says, ‘Oh, a creature.’ In an early story,

Spider-Man apprehends three criminals robbing a store, and the following dialogue

ensues:

Spidey:

“If you’re thinking of putting up a fight, brother, let me warn you . „“

Crook:

“A fight? The only fight I’ll put up is in court. I’m suin’ you for assault and

battery, and I got witnesses to Drove it.” Second crook: “Yeah, that’s right.”

If it is not already perfectly clear that the last vestiges of the

nineteen-forties have fallen away from the world that Spider-Man inhabits, it

becomes so two panels later when.one crook says, right to his face, “Don’t you

feel like a jerk paradin’ around in public in that get-up?”

After overhearing a conversation in another episode between two men who

also apparently consider him a kook, Parker goes home and, unlike any superhero

before him, does some soul-searching. “Can they be right? Am I really some sort

of crackpot wasting my time seeking fame and glory? Why do I do it? Why don’t I

give the whole thing up?”

THE 48-year-old Lee may very well have asked precisely these questions

at some point in his career. He’s been in the business since 1938 when, as a

16-year-old high school graduate, he held some odd jobs (delivery boy, theater

usher, office boy). Then he came to Timely Comics with some scripts and was

hired by editors Joe Simon and Jack Kirby.

For the next 20 years, he labored professionally, but without any

special devotion, to what he thought of as a temporary job. When Simon and

Kirby left, Lee took over as editor as well as writer, and all during the

forties and fifties, mass-produced comic books, 40 or 45 different titles a

month.

“The top sellers varied from month to month, in cycles. Romance books,

mystery books. We followed the trend. When war books were big, we put out war

books. Then one day my wife came to me and said, ‘You’ve got to stop kidding

yourself. This is your work. You’ve got to put yourself into it.’ So I did.

Joanie is the one you really ought to interview. She’s beautiful and talented.

And my daughter, Joanie, who’s 21, she’s also beautiful and talented. I’m a

very lucky guy.”

His wife, he says, is exactly the dream girl he’d always wanted, and he

decided to marry her the first time he saw her. At the time she was married to

another man, but that hardly deterred him. For something like 25 years, the

Lees lived a quiet domestic life in Hewlett Harbor, L. L, before recently

moving back into town. Lee is nothing if not a devoted family man. Among his

other self-evident qualities: he enjoys talking about his work. He is in the

office Tuesdays and Thursdays, editing, and at home the other five days of the

week, writing. “I’m the least temperamental writer you’ll ever know,” he says.

“I write a minimum of four comic books a month. Writing is easy. The thing is

characterization. That takes time. The thing I hate most is writing plots. My

scripts are full of X-outs [crossed-out words]. I read them out loud while

writing, including sound effects. ‘Pttuuuu. Take that, you rat!’ I get carried

away.”

The comic industry has treated Lee very well. He is now, he says, in the

50 to 60 per cent income tax bracket, and he has a very high-paying, five-year

contract with Cadence Industries, which bought Magazine Management Company from

Goodman some 21/2 years ago. When the contract expires, he says, he’s not sure

what he’ll do. He has the vague discontent of a man looking for new fields to

conquer, or, to use another simile, the look of a superhero adrift in a world

that no longer wants him to solve its problems.

Last

year he solved a recurring problem for industry workers by helping to form the

Academy of Comic Book Artists:

“I felt that the publishers themselves weren’t doing anything to improve

the image of the comic books, so I thought, why don’t we do it? Also I wanted

to leave it as a legacy to the industry that has supported me over 30 years.”

The academy now has as members about 80 writers, artists and letterers.

I attended one of their recent meetings, held at the Statler Hilton Hotel in

the Petit Cafe, a barren, pastel-blue and mirrored room with about 200 gray

metal folding chairs with glass ashtrays on them, and a gray metal long table

with glass ashtrays and a lined yellow pad on it.

Around

the room, leaning on gray folding chairs, were “story boards” from comic books

that have been nominated for this year’s awards, which are to be called

Shazams.

Sketches of the proposed designs for

the Shazams were being passed around, most of them serious renderings of the

jagged bolt of lightning that accompanied Billy Batson’s transformation. One,

however, represented a side of comic book artistry that the tans rarely see: A

naked young woman, bent forward at the waist, stands upon the pedestal, while

the airborne Shazam lightning bolt strikes her in the rear. She has a look of

unanticipated delight upon her face.

There were about 30 men present, and one or two young women. Among the

artists and writers I spoke to, there was general agreement that working in the

comic-book industry was not all magic transformations of unworthy flesh.

Problems mentioned as organic included the lack of economic security, the

inability of the artists to keep control over their material, insufficient

prestige and a catch-all category that is apparently the source of abiding

resentment: publishers who do not treat them as serious artists.

As for the censorship of the Comics Code Authority, virtually everybody

agreed they wanted more freedom. Younger writers, in fact, are bringing fresh

ideas into the field. But, as 33-year-old .Archie Goodwin, who writes “Creepy

Comics” for Jim Warren Publishers, wryly observes, the real problem is

self-censorship: “The truth is, maybe half the people here wouldn’t do their

work any different if they didn’t have censorship.”

It did seem to me as I observed the

crowd that there was perhaps more than a random sample of serious-purposed

people who spoke haltingly, with tendentious meekness. The meeting began with

nominations for A. C. B. A. officers for the coming year. I gleefully

anticipated some earth-shaking confrontations between good and evil, but none

developed. Nobody slipped off to a telephone booth to change. The two

nominations for president, Neal Adams and Dick Giordano, by coincidence,

jointly draw the Green Lantern-Green Arrow book for National. Lantern and Arrow

have been squabbling lately, but Adams and Giordano were not at all

disputatious.

In

the entire group I was able to uncover only a single WIC ret life.

“This is my secret life,” Roy Thomas admitted. “Or rather it was, when I

was a teacher at Fox High School in Arnold, Mo.” Thomas, a bespectacled

30-year-old who wears his corn-silk hair straight down almost to the shoulders,

edits at Marvel. “After school hours, I was publishing a comic’s fanzine called

Alter Ego. I spent all my time at night working on Alter Ego.”

“The people in this business,” Lee said to me after the meeting, “are

sincere, honorable, really decent guys. We’re all dedicated, we love comics.

The work we do is very important to the readers. I get mail that closes with,

`God bless you.’ Most of us, we’re like little kids, who, if you pat us on the

head, we’re happy.”

All in all, add a little touch of

resentment, discontent and a pinch of paranoia to Lee’s description and you

have the modern-day comic book superhero. Lee himself has only one frustration

in a long, satisfying career:

“For years the big things on campus have been McLuhan and Tolkien, and

Stan Lee and Marvel, and everybody knew about McLuhan and Tolkien, but nobody

knew about Marvel. Now our competitor is coming out with ‘relevant’ comics and

he has big public relations people, so he’s been easing in on our publicity.”

RELEVANCE is currently such a lure that even industry classics like

Archie are having a stab at it. John Goldwater, president of Archie Comics,

says that Archie definitely keeps up with the times, and offers as evidence

Xerox copies of a silver print, which is an engraver’s photographic proof of an

original drawing. It was of a recent six-pare Archie story entitled, “Weigh Out

Scene.”

“This is a civil-rights story,” Goldwater said. “It’s clone subtly. It

has to do with a fat boy who comes to town who can’t fit into the mainstream

with the teen-agers in town. Because of his obesity, he’s taunted and

humiliated. You know how kids are. Then one night Archie has a dream. And in

this dream he is obese and fat and everybody is taunting him and ridiculing him

and now he finally realizes what happened to this poor kid. So then there is a complete

turnaround. But we don’t say, remember, this kid is black. We don’t say that.

But the subtlety is there.”

Goldwater, who is also president of the Comics Code Authority is

convinced that “comics don’t ruin your mind.” He says: “1 wouldn’t be in this

business unless it had some value, some educational value. If you can get a kid

today to read, it’s quite some victory — instead of him looking at the boob

tube, you know?”

Recently there were some ruffled feelings in the industry- when Marvel

issued a comic book without the authority seal, which was denied because the

subject of drugs was alluded to in one story that showed a stoned black kid

tottering on a rooftop. Goldwater felt that hinted a hit of sensationalism, and

Infantino believes the subject calls for a more thorough and responsible

treatment. Lee scoffs. Black kids getting stoned isn’t exactly a biannual

occurrence, he suggests. Goodman calls the fuss a tempest in a teapot.

Goldwater, at any rate, is not inclined .to be harsh:

“Goodman came before the publishers and promised not to do it again. So

we’re satisfied. Anybody with 15 solid years of high standards of publishing

comic books with the seal is entitled to one mistake.”

Subsequently the publishers agreed

to give themselves permission to deal with the subject. “Narcotics addiction,”

says the new guideline “shall not be presented except as a vicious habit.”

GOODMAN is not so sure relevance will continue to sustain sales, but

Infantino is elated at National’s success with social issues.

National turned toward relevance and social commentary for the same

reasons Marvel had a decade earlier. “I’d like to say I had a great dream,”

says Infantino, “but it didn’t happen that way. Green Lantern was dying. The

whole superhero line was dying. Everything was sagging, everything. When your

sales don’t work, they’re telling you something. The front office told me, get

rid of the book, but I said, let me try something, just for three issues. We

started interviewing groups of kids around the country. The one thing they kept

repeating: they want to know the truth. Suddenly the light bulb goes on: Wow,

we’ve been missing the boat here!”

In the first of National’s relevant books, which came out in the fall of

1970, Green Lantern comes to the aid of a respectable citizen, besieged by a

crowd, who turns out to be a slum landlord badly in need of a thrashing.

Lantern is confused to discover his pal Green Arrow actually siding with The

People. “You mean you’re . , . defending ... these ... ANARCHISTS?” he says.

Following a tour of the ghetto, Green Lantern is finally brought face to

face with reality by an old black man who says: “I ‘ve been readin’ about you,

how you work for the Blue Skins, and how on a planet someplace you helped out

the Orange Skins .., and you done considerable for the Purple Skins. Only

there’s Skins you never bothered with. The Black Skins. I want to know ... how

come? Answer me that, Mr. Green Lantern.”

This

story, written by 28 year-old Denny O’Neil, is one of the nominees for -the

writing Shazam, and the consensus of opinion, even among rival nominees, is

that he’ll win it. In the following months, O’Neil had the superheroes on the

road discovering America and taking up such provocative current issues as the

Manson family, the mistreatment of American Indians, the Chicago Seven trial,

and, finally, in a forthcoming issue, the style and substance of the President

and Vice President.

Mr. Agnew appears as Grandy, a simpering but vicious private-school cook

whose ward is a certain ski-nosed child-witch named Sybil. A mere gaze from

Sybil can cause great pain; one look from her and even Arrow and Lantern double

over in agony. That certainly is making things clear. Grandy is constantly

justifying his nastiness: “Old Grandy doesn’t kill. I simply do my duty. Punish

those who can’t respect order. You may die. But that won’t be my fault.”

“What we’re saying here,” says Infantino, “is, there can be troubles

with your Government unless you have the right leaders. Sure, we expect flak

from the Administration, but we feel the kids have a right to know, and they

want to know. The kids are more sophisticated than anyone imagines, and we feel

the doors are so wide open here that we’re going in many directions.

“You wouldn’t believe whom I’m

talking to. Big-name writers — and they’re interested. We have innovations in

mind for older audiences, and in graphics we’re going to take it such a step

forward, it’ll blow the mind.” He was so excited during our talk that he stood

up. “We’re akin to a young lady pregnant and having her first baby.” He grinned

shyly.

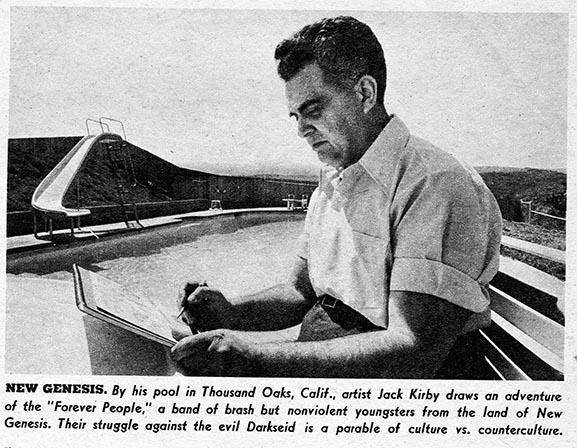

THE artist who has produced the most innovative work for Infantino is

53-year-old Jack Kirby, about whom Stan Lee says: “He is one of the giants, a

real titan. He’s had tremendous influence in the field. His art work has great

power and drama and tells a story beautifully. No matter what he draws it looks

exciting, and that’s the name of the game.”

Unlike the “relevant” comic books, Kirby’s new line eschews

self-conscious liberal rhetoric about social issues and returns to the basic

function of comic books: to describe in an exciting, imaginative way how power

operates in the world, the struggle to attain it by those who lack it and the

uses to which it is put by those who have it.

Kirby began to conceive his new comic books when he was still at Marvel,

but felt he might not get enough editorial autonomy. He left his $35,000-a-year

job at Marvel and took his new books to National. He also moved from New York

to Southern California, where he edits, writes and draws the books.

His new heroes are the Forever People, whom he describes as “the other

side of the gap — the under-30 group. I’m over 50. I’ve had no personal

experience of the counterculture. It’s all

from the imagination.”

The Forever People arrive on earth through a

“boom tube,” which is an attempt to offer approximate coordinates for an

experiential conjunction of media wash and psychedelic trip. They are said to

be “In Search of a Dream.” There are five of them: one is a relaxed,

self-assured, young black man who, probably not by accident, carries the

group’s power source, known as the “mother box”; another is a shaggy-bearded

giant who overwhelms his small-minded taunters with a loving, crushing bear

hug; the third, a beautiful saintly flower child named Serafin is called a

“sensitive”; the fourth, a combination rock star-football hero transmogrified

into one Mark Moonrider; and the fifth, a girl named Beautiful Dreamer.

The mother box, which warns them of impending

danger, also transforms them — not into five distinct, ego-involved superheroes

but into a single all-powerful Infinity Man, who comes from a place where “all

of natural law shifts, and bends, and changes. Where the answer to gravity is

antigravity — and simply done.”

These new heroes, unlike the characters of the

sixties, are brash, confident youngsters whose superpower lies in their ability

to unify. They are also, says Kirby, “basically nonviolent.”

Infantino has been asked up to Yale to talk about

Kirby’s new books, and to Brown, for the new course in Comparative Comics.

Students in Comp. Coin. I will doubtless relish Kirby’s toying with words like

“gravity” (and other mild Joycean puns sprinkled elsewhere) to suggest elements

of his loadable of culture vs. counterculture. Suffice it to say here that the

Forever People are from New Genesis, where the land is eternally green and

children frolic in joy, and their enemy is Darkseid, who serves “holocaust and

death.”

The story of New Genesis is also told in another

new Kirby book called “New Gods.” When the old gods died, the story goes, the

New Gods rose on New Genesis, where the High-Father, who alone has access to

The Source, bows to the young, saying, “They are the carriers of life. They

must remain free. Life flowers in freedom.”

Opposed

to New Genesis is its “dark shadow,” Apokolips, the home of evil Darkseid and

his rotten minions. Darkseid’s planet “is a dismal, unclean place of great ugly

houses sheltering uglier machines.” Apokolips is an armed camp where those who

live with weapons rule the wretches who built them. Life is the evil here. And

death is the great goal. All that New

Genesis stands for is reversed on Apokolips.

Darkseid has not, of course, been content to rule

on Apokolips. He wants to duplicate that horror on, of all places, Earth, and

he can do this if he manages somehow to acquire the “antilife equation.” With

it, he will be able to “snuff out all life on Earth — with a word.”

Thus is the battle drawn, and the

Forever People, notably, are not going to waste their time hassling with

raucous hardhats who don’t understand the crisis. When a hostile, paranoid,

Middle-America type confronts them, they arrange it so that he sees them just

about the way he remembers kids to have been in his own childhood: Beautiful

Dreamer wearing a sensible frilly dress down to her knees, the cosmic-sensitive

Serafin wearing a high-school sweater and beanie, Moon-rider with hat and tie

and close-cropped hair.

“What’s

going on here? You kids look so different—and yet so familiar.”

“Why

sure,” says Beautiful Dreamer soothingly. “You used to know lots of kids like

us. Remember? We never passed without saying hello.”

In the titanic struggle against Darkseid, the Forever People have lots

of help, and they are beginning to populate four different comic books:

“Forever People,” “New Gods,” “Mister Miracle” and “Superman’s Pal Jimmy

Olsen.” Both Superman and Jimmy Olsen are being altered to fit the evolution of

Kirby’s Faulknerian saga of the difficult days leading to Armageddon. Already

identified in the Kirby iconography on the side of the good are the newly

revived and updated Newsboy Legion, so popular in the nineteen-forties; various

dropout tribes living in “The Wild Area” and “experimenting with life” after

harnessing the DNA molecule; and a tribe of technologically sophisticated

youths called “Hairies,” who live in a mobile “Mountain of Judgment” as

protection against those who would destroy them. “You know our story,” says one

Hairy. “We seek only to be left alone—to use our talents, to develop fully.”

On the other side, in support of Darkseid are middle managers and

technocrats of the Establishment, like Morgan Edge, a media baron who treats

his new employee Clark Kent—now a TV newscaster—abominably.

Darkseid’s lousy band also includes an assortment of grotesque super

villains. Among them are DeSaad and his terrifying “Fear Machine,” and a

handsome toothy character named Glorious Godfrey, a revivalist. Godfrey is

drawn to look like an actor playing Billy Graham in a Hollywood film biography

of Richard Nixon starring George Hamilton.

“I hear you right thinkers,” Godfrey says to his grim, eyeless audience

of true believers, “You’re shouting antilife—the positive belief.”

In

the background acolytes carry signs: “Life has pitfalls! Antilife is

protection!” And, “You can justify anything with antilife!” And, “Life will

make you doubt! Antilife will make you right!”

I HAVE no final answers,” Kirby admits. “I

have no end in mind. This is like a continuing novel. My feeling about these

times is that they’re hopeful but full of danger. Any time you have silos

buried around the country there’s danger. In the forties when I created Captain

America, that was my feeling then, that patriotism. Comics are definitely a

native American art. They always have been. And I’m feeling very good about

this. My mail has been about 90 per cent positive, and sales are good.”

Infantino adds:

“The kids at Yale think Kirby’s new books are more tuned in to them than

any other media. They’re reading transcripts from ‘New Gods’ over their radio

station. The Kirby books are a conscious attempt to show what things look like

when you’re out where the kids are. The collages, the influence of the drug

culture. We’re showing them basically what they’re seeing. We’re turning into

what they’re experiencing.”

If that is true—and I am not so sure it isn’t—then perhaps the rest of

us had better begin choosing sides. New Genesis anyone?

One week later, a letter to the editor: How

Relevant are COMICS?

TO THE EDITOR:

The

elevation of comic art beyond its value began with the introduction and

acceptance, of the pop art concept, Saul Braun's article, "Shazam! Here

Comes Captain Relevant' (May 2), will do much to lift, still further, an

industry already giddy with its own sense of importance. The featured cover,

alluding to the massacre at Mylai, is an excellent example of how comic heroes

"ponder moral questions," Pander is surely more to the point.

It is exactly this treatment of real

issues that corrupts the meaning of relevance. This corruption is intrinsic in

Martin Goodman's uncertainty as to whether "relevance will continue to

sustain sales." If it doesn't, of course, other rationales will be sought

to define the importance of comics —just as they were found to justify the

incredible excesses of horror comics when they sustained sales.

Of course, comics have value, but it

will not be defined by a man who finds himself "unable to believe that the

worst comic books could have corrupted the child's mind as much as [my italic]

the knowledge that . . . in the world he was being educated to join, 6 million

men, women and children had only recently been killed in gas ovens for no very

good reason."

For heaven's sake, Mr. Braun.

ERNESTO COLON Cartoonist.

New York

" Lee’s comic antiheroes (Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, Submariner, Thor, Captain America)"..

ReplyDeleteNever heard of Jack Kirby, Joe Simon or Bill Everett, then, Saul?

Would your paper's coverage of the election the next year be as accurate as this? Ever heard of Watergate?

As Marvein Gaye sang around this time: Makes me wanna holler, throw up both my hands.

ReplyDeleteFirst, this has nothing to do with Watergate which the Times handled pretty damn well. As well as the election. This was not as as important. And I will not equate this article, by SAUL BRAUN who the Times says in the very beginning is a freelance writer,not a Times writer, to some great journalistic error. This actually means that the Times, which did not have a comic section, knew nothing about comics.

I have written about this before and it shows two sad points however. That is the reporters of this era, perhaps 1965-75, simply did not think an article about comics deserved research. Everyone who just read comics was an authority!!! They would not think that about any other part of popular culture, music, TV or movies. At least this guy read comics, most of the reporters of the day did not. So they pick up on the easy story, Stan Lee.

The other sad thing is that Stan did not write the article, he was one of the several people being interviewed, yet he often got the blame for this incomplete reporting. Here, they interview Kirby and still don’t give him “co-creator” status, that is not Stan’s fault. But often he got the blame for something he didn’t write.