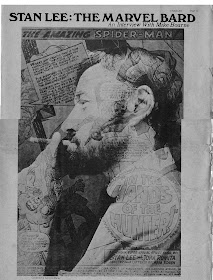

Stan Lee, the Marvel Bard: An Interview with Mike Bourne from Changes Magazine April 15, 1970.

BUT First! I would like to thank the people who made the post possible: The Incredible Nick Caputo and the Mighty Dusty Miller! Thanks guys!

Marvel Comics spring from modest Madison Avenue offices randomly decorated by oversize drawings, copy, and other assorted fanciful diversions. In several small cubicles like freaky monks, a staff of artists variously evoke the next month’s adventures in all brilliant colour and style. While in his office, his complete Shakespeare close at hand, editor Stan Lee smiles broadly behind his cigar and beckons me enter his head. .

MIKE: With which superhero do you personally most identify?

STAN: Probably Homer the Happy Ghost. You know, I honestly don’t identify with any of them. Or maybe I identify with all of them. But I’ve never thought of it. I’ve been asked this question before and I never know how to answer it because I think I identify with whichever one I’m writing at the moment. If I’m writing Thor, I’m a Norse god at that moment. If I’m writing the Hulk, I have green skin and everyone hates me. And when I stop writing them, they’re sort of out of my mind. I’m not identifying with anyone.

MIKE: You’re like an actor when you write.

STAN: Yeah, I think more than anything. In fact, when I was young I thought I would be an actor, and I did act. And when I write now, my wife always makes fun of me. She says: “Stan, what did you say?” I say: “Nothing, I’m writing.” She says: “Well, you talk to yourself.” And I find very often I’m saying the lines out loud. And I’m acting! You know: “Take that, you rat!”

MIKE: Asking a writer where he gets his ideas is like asking an actor how he learned all those lines, but Marvel is known as the House of Ideas.

STAN: Only because I originally said we were the House of Ideas.

MIKE: Alright, but obviously you have mythological influences. And Jim Steranko’s “House of Ravenlock” for S.H.I.E.L.D. was very much from the Gothic novel. But what are your primary sources, or your favorite sources for material? Just out of your head, or where?

STAN: Mostly. I think it all has to do with things I read and learned and observed when I was young, because I don’t do as much reading or movie going, or ,anything now as I would like. I’m so busy writing all the time. But I was a voracious reader when I was a-teenager. And actually I think my biggest influence was Shakespeare, who was my god. I mean, I loved Shakespeare because when he was dramatic, no one was more dramatic than he was. When he was humourous, the humour was so earthy and rich. And everything. To me he was the complete writer. I was just telling somebody this morning who was up here to try to do some writing for us to get as close to Shakespeare as possible. Because whatever Shakespeare did, he did it in the extreme. It’s almost like the Yiddish Theatre. When they act, they act! Or the old silent movies where everything was exaggerated so the audience would know what the mood was because they couldn’t hear the voices. So. actually, as I say, I used to read Shakespeare. I love the rhythm of words. I’ve always been in love with the way words sound. Sometimes I’ll use words just because of the sound of one playing upon the other. And I know comic book writers aren’t supposed to talk this way. But I like to think I’m really writing when I write a comic, and not just putting a few balloons on a page.

MIKE: Do you consciously strive to catch the tenor of the times? You’ve covered campus protest in Spider-Man. But what about other issues? Do you feel that it’s your responsibility as an artist — and I won’t say “comics” artist here, but obviously we can accept you as an artist with other kinds of artists — is it your duty to take a stand on issues?

STAN: I think it’s your duty to yourself really, more than to the public. See, this is a very difficult field. For years my hands were tied. We thought we were just writing for kids, and we weren’t supposed to do anything to disturb them or upset their parents, or violate the Comics Code and so forth. But over the years as I realized more and more adults were reading our books and people of college age (which is tremendously gratifying to me), I felt that now I can finally start saying some of the things I would like to say. And I don’t consciously try to keep up with the tempo or the temper of the times. What I try to do is say the things I’m interested in. I mean, I don’t want to write comics. I would love to be writing about drugs and about crime and about Vietnam and about colleges and about things that mean something. At least I can put a little of that in the stories. As I say, tho, I’m really doing it for myself, not the reader. But everybody wants to say what he thinks_ And if you’re in the arts, you want to show what you believe. r think that’s pretty natural.

MIKE: What do you consider your responsibility as a comics artist then?

STAN: To entertain. I think comic books are basically an entertainment medium, and primarily people read them for escapist enjoyment. And I think the minute they stop being enjoyable they lose all their value. Now hopefully I can make them enjoyable and also beneficial in some way. This is a difficult trick, but I try within the limits of my own talent.

MIKE: Several years ago, Esquire published a collage of the “28 Who Count” on the Berkeley campus, and included were the Hulk and Spider-Man. What’s this great appeal of Marvel Comics to college students?

STAN: I don’t know. I would think the fact that there’s a sort of serendipity, there is surprise. You don’t expect to find a comic book being written as well as we try to write Marvel. You don’t expect to find a comic book that’s aimed at anyone above twelve years old. And I think a college kid might pick up a Marvel Comic just to idly leaf thru it and then a big word catches his eye. Or a flowery phrase or an interesting concept. And before he knows it, not every college kid, but a good many of them are hooked. And I think it’s the fact that here is something which has always been thought .of as a children’s type of diversion. And they realize: “My God! I can enjoy this now!” This is kind of unusual.

MIKE: It’s like the end of the one Avengers story when you used “Ozymandias” to reinforce the villain’s downfall.

STAN: Wasn’t that great? That was Roy Thomas’ idea, one of the best he’s ever had. Beautiful ending that way;

MIKE: I’ve always wondered that perhaps the appeal is the catalogue of neuroses in the superheroes. That they’re all into the numbers people are going thru now. Human fallibility, altruism, identity crises, these sorts of things. Like even your arch-fiends like Dr. Doom and the Mandarin and Galactus are not really all bad. They’ve all been forced to be bad, to be misanthropes, by force of circumstances. But when’s sex going to come into Marvel Comics?

STAN: Unfortunately not until we get rid of the. Comics Code, or put out a line strictly for adults (which I’ve been wanting to do). But I just haven’t been able to convince the powers that be that the world is ready for them yet.

MIKE: Well obviously you’ve broken some barriers by having heroes married and having children.

STAN: Hopefully someday we’ll be able to put out a line — not that we want to do dirty books — but something that’s really significant and really on the level of the older reader.

MIKE: I recall one thing that wigged me in that regard: the beginning of a Nick Fury story where it was morning with a subtle hint of the previous night’s activities.

STAN: Oh yes, that was Jim Steranko’s. Wasn’t that great? I was very pleased that it got past the Code. Well, actually you had to be smart enough to grasp that. But that’s part of these stories. I think it’s utterly ridiculous to shield our readers from things in comic books which they see all around them.

MIKE : Where are you going on the race issues? I read, of course, where the Black Panther character pooped out because of the real Black Panthers emerging.

STAN: Yeah, that was very unfortunate. I made up the name, Black Panther, before I was conscious that there is a militant group called the Black Panthers. And I didn’t want to make it seem that we were espousing any particular cause. And because of that we’re not able to push the Panther as much, altho we’re still using him.

MIKE: Well, also it would have been strange to have a black superhero who is also the richest man in the world.

STAN: Yeah, so the whole idea was a little bit off. I told Roy Thomas what I’d like to do with him is have Roy write the Panther so he teaches underprivileged children in the ghetto and uses his own knowledge and his own force and leadership to help these kids.

MIKE: How about the Falcon as a black superhero?

STAN: Now I think we have a better chance with the Falcon. We’ve used him in three stories, then we dropped him, and I want to wait and see how the mail comes in. I’m hoping it’ll be good and I’d like to give him his own book. I’d like to just make him a guy from the ghetto who is like Captain America or Daredevil. No great super power, but athletic and heroic. And let him fight for the cause that will benefit his own people. I would have done this years ago, but again the powers that be are very cautious about things and I can’t go leaping.

MIKE: How serious or how deep is the religious allegory in the Silver Surfer?

STAN: I think pretty unconsciously. I’m really just trying to write something kind of poetic and kind of pretty and kind of mystical sounding. I think youcan read a lot into it. In fact, when I discussed the character with John Buscema before he started drawing the book, John said: “Well, how do you want me to think of him? You know, what kind of guy?” And I said: “The closer you come to Jesus Christ the better.” He has that kind of a personality. He’s almost totally good, unlike most of our heroes, and I’m enjoying doing the Silver Surfer.

MIKE: But why “Surfer”?

STAN: Actually, we’re stuck with the name, because when he first appeared, he appeared as an incidental character in a Fantastic Four story. Jack Kirby just threw him in — I think the name was Jack’s — and called him the Silver Surfer. I thought it sounded good and used him. Had I known that we would end up doing with him what we’re doing today, I would have taken more pains to get a name that was more applicable. But actually, nobody else seems to mind the name. It’s easy to remember and it’s almost a put-on. And I haven’t had any complaints about it.

MIKE: My walls and ceiling are papered with Marvel Comics covers, and one cat came in one day and said “This is the most violent wall I’ve ever seen!” What about violence in Marvel Comics?

STAN: I don’t know. What the hell is violence? I don’t think our books are violent at all. I think our books are the exact opposite of violence. I don’t like to say this because it’s become a cliche by now, but real life is violent. I mean crime, Viet Nam, poverty, and bigotry are violent. There’s nothing violent in our books: good guys trying to save the world from bad guys. If somebody punches somebody in a story, we throw it in because the kids wouldn’t buy the book unless we did. Frankly, it’s our concession to the younger readers. There has to be a fight scene somewhere. Just like you’re not going to get any young kids to go to a western movie unless there’s one or two shootings. But compared -to the problems

of the world today, I don’t consider a punch in the jaw really violent as we do it. Even there it isn’t a normal punch in the jaw. It’s usually one invincible human being hitting an indestructible creature of some sort. You don’t even get the feeling anyone’s jaw is getting broken as it might happen in real life. It’s all so totally fictitious and so totally fanciful that it isn’t what my conception is of violence. I would call it exciting and fast-moving and imaginative. But I really wouldn’t call it violent.

MIKE: How do you feel about the gory publications that exploit violence? Those where you see spikes thru young girls and blood spurting all over?

STAN: Well, that’s what killed comics years ago. We don’t do anything like that. It doesn’t particularly bother me. I think it’s in bad taste. There’s so much to be said and there’s so many ideas to be brought forth that you just don’t need all that gruesome stuff. And you don’t need all the dirty stuff. It almost dilutes the message. Nothing wrong with good horror stories, but you just don’t need the things that are in such bad taste that you don’t even appreciate that maybe the story was good beyond that.

MIKE: Do you feel that you romanticize war in Sgt. Fury?

STAN: It is possible. I haven’t written Sgt. Fury for years now. I wrote the first few. And in the beginning I did not try to make war look glamorous at all. I don’t think the people who are writing the book now are trying to make war look glamorous. But, of course, it can always come across that way. It’s not our intention. If it does come across that way, it means we’ve slipped. We are certainly not pro-war, not pro any kind of war. And we try, even in those books, to point out little morals. We try to speak out against bigotry and other things. But any story you do that’s a war story, no matter how carefully you do it, it’s going to seem as if you’re romanticizing war. Maybe if we did nothing but that one book and took the greatest care and spent a whole month creating a plot and making sure we plugged all the loop-holes, we could let the book stand as a tremendous indictment. But in order to make the book an indictment against war and to make it as horrible as it would have to be, we wouldn’t be able to get past the Code office. Because we’d have to show the horrors of war. So we’re kind of stuck there. We can’t show violent deaths or anything like that. And Sgt. Fury is just something we publish and some people buy it and I don’t think it’s really doing any harm. And I try not to think about it too much.

MIKE: Another thing I’ve noticed that might explain Marvel’s kind of appeal is all our contemporary fears of annihilation, from one thing or another. Almost every month your world is about to be destroyed, or at least it’s in peril some way. But we always know it’s going to be saved and that tension is relieved. Except that we know in real life there’s no super-hero to save us.

STAN: Well, I think we all like to think that there are superheroes in real life. I think we all wanted to think that John Kennedy was a superhero. Franklin Roosevelt before him. Maybe Bobby Kennedy. For a short time we hoped that McCarthy would be a superhero. I think that the human race needs superheroes, and whether, they’re fictional or not — obviously a real live one would be more satisfactory — I think if we don’t have them, we’re almost forced to create them. Because I think we’re all consciously or unconsciously aware that the problems that beset us are just too big and too grave to be solved by ourselves. And we can either throw up our hands and figure that nothing is going to help, or we can figure that somehow somewhere someone knows more than we.

MIKE: What’s the power of comic books?

STAN: Your guess is as good as mine. That’s the thing, the one thing I’m not an authority about, is anything that happens after the book leaves this office. It’s the power of anything that influences the people who read it. Human beings are influenced by everything they see, hear, touch, taste, smell. We sell about sixty million copies a year. And if millions of kids and adults read these books every year, then they must have some power to influence them, to shape their thoughts a little bit. It’s like saying what’s the power of movies, or what’s the power of anything.

MIKE: But you do have this fanciful medium which would be perfect for moralizing.

STAN: I try to moralize as much as possible. I’m always a little nervous and hope I’m not overdoing it and turning people off. But maybe I’m naturally half a preacher at heart. I find I enjoy it. And it’s funny because it seems that people enjoy it. Like I used one phrase in a Fantastic Four story once: “In all the universe there is only only being who is all powerful.” Somebody was talking about this all powerful character having a great weapon. And I think it was the Watcher answered by saying there is only one who is truly all powerful and his greatest power is love. I must have gotten five hundred million letters about that, saying how great that was and how it brought a tear to their eye and a lump to their throat and why isn’t there more of that stuff in the comics. I may become the Lawrence Welk or, more probably, the Billy Graham of the comic book business.

MIKE: Can you think of particular elements that mark Marvel Comics more than typical escape literature? I suppose it’s all these things we’ve been talking about.

STAN: Well, I hope it is. And if it is, I would think —in music you might call it soul — maybe we put a to me. And I know there are reasons why these things are done. But I think what a damn shame it is that all that talent isn’t used on something that doesn’t have to be quite so vulgar, which is the only word for it. I sometimes think, as with the underground newspapers too, that they very often use vulgarity in place of quality, in place of something meaningful. And I know it is all done for the shock value and there are millions of reasons. But I know that after the first flush of the underground surge is over, then I think these papers and these strips will begin to take their rightful place and really show the talent that’s behind them, which I think is kind of hard to find in many cases now.

MIKE: How big a business is Marvel Comics?

STAN: Well, our subscriptions are high, and we lose money on them. It costs too much to process them and mail them out. As far as how big it is, as I say, we sell about sixty million copies a year, and that’s pretty big.

MIKE: What age figures are your major consumers?

STAN: Rough guess: about sixty percent of our readers are under sixteen and about forty percent are over sixteen. We have an adult audience of a magnitude that comics have never had before. I’ve lectured at a dozen colleges. And rye been invited to over a hundred colleges, but I just didn’t have. the time to go. And I don’t say that every college is hipped to Marvel. But in every college there is a nucleus of students who are big Marvel buffs, which is great.

MIKE: Before I came, I interviewed a Marvel freak, who had been a Marvel freak at Berkeley. And he’s become very disillusioned with you lately and says that a lot of the Berkeley radicals who first went into Marvel Comics are becoming very disillusioned for several reasons. For one, he thinks you’ve lost the simplicity that you had at one time, that you’ve become so complex you’re taking yourself too seriously. And he mentioned like the Sandman changing from the polo shirt to a more exotic outfit. And Paste-Pot Pete no longer the sort of funny character he was, but now the Trapster. He figures they’ve lost the easy identification.

STAN: Well, it’s a funny thing. We only did that last for one reason, We didn’t sell enough copies when we used Paste-Pot Pete. I made up the name and loved it. I. thought: there’s never been a villain called Paste-Pot Pete. It was great, and it didn’t take itself seriously. It was all tongue-in-cheek. Whoever had a Paste Gun? But the older readers loved it and the little kids — it wasn’t dramatic enough for them. So, we’re still a business. It doesn’t do us any good to put out stuff we like if the books don’t sell. And the Trapster attracted the younger kids, sounded more dramatic. I don’t like it as much. We had a story once in Fantastic Four called “The Impossible Man.” He was a funny little guy from the Planet Pop-Up, and he could do anything. He could turn himself into a buzz saw, and he gave the FF one of their hardest fights. And I loved him, and he was humourous and really far out, and the older readers were crazy about him. And that was the worst selling Fantastic Four we’ve ever had. Because he was too unusual and too frivolous for the very young kids and it made me realize, unfortunately, that I can’t get too far out on these stories, or we just don’t sell enough copies.

MIKE: The second objection was that he accused you of selling out to kids.

STAN: Well, I try not to. But I would gain nothing by not doing the things to reach the kids, because I would lose my job and we’d go out of business.

MIKE: So where are you now heading?

STAN: I don’t know where we’re heading. Each say I get a new idea or somebody has a new suggestion. We have trouble just keeping our balance and meeting all our deadlines. It’s a mad scramble. I’m sitting here looking, I imagine, rather relaxed now. But you’ve no idea. It’s just panic all day long. We don’t know from day to day what we’re gonna do tomorrow. It’s just whatever hits us. I would like to think we could come up with a million new ideas. I hate to sit still. And we have been sitting still too long. The only reason we’re putting out these kid’s books and things like that now is that business has gotten a little soft. There’s a little bit of a slump and those are a little more inexpensive to put out. So it brings the whole overhead down a little by turning those out and enables us to continue the good stuff.

MIKE: I’ve asked you where you’re heading. So, where have you been? What do you feel you have achieved as an artist in your career? The most satisfying aspect?

STAN: I don’t know. I guess maybe the single most satisfying thing may be that I’ve been somewhat responsible for elevating — I hope I’ve been — for elevating comics a little and taking them out of the realm of reading matter that was deemed to be just for little kids. And making comics reach the point where somebody like you would be interviewing me about it. I think that’s a hell of an accomplishment. Because it wasn’t an easy thing to do. I think there’s probably a lot more I could have done and I hope I’ll live long enough to do a lot more. I don’t think I’ve really done that much. This is like the guy on the moon: it’s a first step.

MIKE: Obviously you have lifted a popular diversion to not only a major business but also a very widespread influential art form. But what is the legacy of Stan Lee?

STAN: I don’t know. The only thing that bothers me about the question is that it makes it sound like the story is over. I have a couple of more years to go. A lot of people think I’ve started a certain style of writing, and when new writers come up here they say “I think I could write in your style.” I don’t know what the hell my style is. I think I write in a lot of different styles, depending upon what book I’m writing. And, you see, there’s another funny thing: people lose interest very quickly the minute something becomes too successful. People look for something new. And I think we’re entering a phase where we’ve got to start coming up with new things. Because, otherwise, Marvel’s had it. I mean, there was a time that it was very clever and very “in” to discover Marvel. Now everybody knows about Marvel, so now people are looking for something else to discover. I would like to keep moving with that crest, but in a slightly different area for them to keep discovering us. So I don’t think we can ever stop. I hope we’ll have all kinds of surprises for you in the next year or two, next time you come

And just as I packed up my recorder , a plot crisis with Roy Thomas sent Smilin’ Stan once again into the search for our future marvels.

MARVEL Comics

Pow! ZOOOOOM! WHAM!!!

Pow! ZOOOOOM! WHAM!!!

"One Touch of this button and the Earth is mine!"

Magazine articles are syndicated, not just within the country but all over the world. Here is version of the CHANGES article that appeared in Great Britain. Note that the introduction is changed and the reporters name is removed. Also certain words like “color” have been altered for the British “colour.”

Great Britain's IT Magazine: Oct. 8th 1970

From a modest Madison Avenue penthouse suite, decorated with monster piles of copy, outsize cartoon; drawing pins, demented graffitti and other assorted diversionalia. The artists, like freaky monks, each in his small cubicle, create next month’s living-colour action-packed giggle-starred adventure while in his office, editor STAN LEE his ‘Complete Works of Shakespeare close to hand, beams fatly from behind a fat cigar and beckons you into his head . . .

QUESTION: Asking a writer where he gets his ideas is like asking an actor how he learned all those lines, but Marvel is known as the House of Ideas.

STAN: Only because I originally said we were. Mostly it has to do with things I read and learned and observed when I was young. I was a voracious reader when I was a teenager and actually I THINK MY BIGGEST INFLUENCE WAS SHAKESPEARE! He was my God! No one was more dramatic than he was. When he was humorous, the humor was so earthy and rich. He was the complete writer. I was just telling somebody this morning who was up here to do some writing for us to get as close to Shakespeare as possible. Because whatever he did, he did in the extreme. It’s like Yiddish Theatre: when they act, they ACT! Or the old silent movies, with everything exaggerated so the audience would recognize the mood. I love words! I love their rhythm. I’ve always been in love with the way words sound and I know comic book writers aren’t supposed to talk this way, but I like to think I’m really writing when a comic write, and not just putting a few balloons on a page

QUESTION: Do you consciously strive to catch the tenor of the times? You’ve covered campus protest in Spider-Man. But what about other times? Do you feel that it’s your responsibility as an artist - and won’t say ‘comic artist’— is it your duty to take a stand.

STAN: I think it’s your duty to yourself really; more than to the public. See this is a very difficult field. For years my hands were tied. We thought we were just writing for kids and we weren’t supposed to do anything to disturb them or violate the Comics Code and so forth. But user the years, as I raised snore and more adults were reading our books, and people of college age (which is tremendously gratifying to me) felt that now I could start saying some of the things I would like to say. I don’t consciously try to keep up with the tenor of the times. What I try to do is say the things I’m interested in. I don’t want to write comics. I would love to be writing about drugs and about crime and about Vietnam and about colleges and about things that mean something. At least I can put a little of that in the stories. As I say though, I’m really doing it for myself, not for the reader. But everybody wants to say what he thinks. And if you’re in the arts, you want to show what you believe. I think that’s pretty natural.